My interest to explore the EACC comes from its role in linking the boundary currents north of Madagascar and at the equator. It is long established that the East African Coastal Current flows northward along the coast of Tanzania throughout the year1. However, until now we have a rough sketch of the East african coastal current and its seanoal variations. In this post, I am going to illustrate to you how to process drifter data that capture nicely the pathways of the EACC. The EACC must have been known to naviagators for a long time. Its waters form part of a maritime trade routes first described about 1900 years ago2. Compared to the more dramatic reversing Somali Current, the EACC has received relatively little attention from oceanographers.

Early references work in the EACC are given by Lutjerharms3. The EACC is not clearly resolved in the Atlas of the International Indian Ocean Expedition4 nor in the more detailed seasonal charts of Citeau and others5. In this post I used drifter’s observations from Global Drifter Program to highlight the surface current flow of East African Coastal Current (EACC) during the northeast and southeast monsoon season.

Needed Packages

We need to load some packages into R that are used to process the data. The chunk below show the list of packages I selected that I will use to import the data, manipulate, transform and last presented the results in form of maps. One of the package is the tidyverse, which loads five other packages — ggplot2, tibble, tidyr, readr, purrr, and dplyr packages. These are considered to be the core of the tidyverse because are mostly used in almost every analysis.

require(tidyverse)

require(lubridate)

require(leaflet)

require(insol)

require(kableExtra)

require(sf)

require(tmap)Data Manipulation

Once the packages are loaded in R, I used the dplyr’s function read_table2() to import the data into R’s workspace. read_table2() is designed to read the type of textual data where each column is separated by one (or more) columns of space.

## load the dataset

drifter = read_table2("./drifters.txt", comment = "#",

col_names = FALSE)Once the data was in the workspace, I found the data comes without column names and it also contains columns with empty cells. In this case, the first process I did is to rename the variables with appropriate names using the dpyr’s function rename().

drifter = drifter%>%select(id = X1, lon = X2, lat = X3,

drogue = X4, u = X5, v = X6,

sst = X7, year = X8, month = X9,

day = X10, hour = X11)Because the monsoon season affects the surface current circulation in the tropical Indian Ocean Region, I create a seasonal variable from the month variable and computed the surface current velocity based on the equation (1).

\[ \begin{equation} Velocity \:(ms^{-1})\:=\: \sqrt{(U^2+V^2)} \tag{1} \end{equation} \]

Creating Trajectory

I used sf package that implements a formal standard called “Simple Features” that specifies a storage and access model of spatial geometries (point, line, polygon). A feature geometry is called simple when it consists of points connected by straight line pieces, and does not intersect itself. Using the unique identification number of drifters, point features were created first and then transformed into trajectories.

## create simple features

drifter.sf = drifter%>%

select(season, id, lon,lat ,u,v)%>%

mutate(velocity = sqrt(u^2 + v^2))%>%

st_as_sf(coords = c("lon", "lat"))%>%

st_set_crs(4326)

## create trajectory

drifter.traj = drifter.sf%>%

group_by(id, season)%>%

summarise(vel = mean(velocity, na.rm = TRUE), do_union = FALSE)%>%

st_cast("LINESTRING")

# drop some trajectory with one point

drifter.traj = drifter.traj%>%filter(id != 52950 & id != 9421944 & id != 9918672)Results

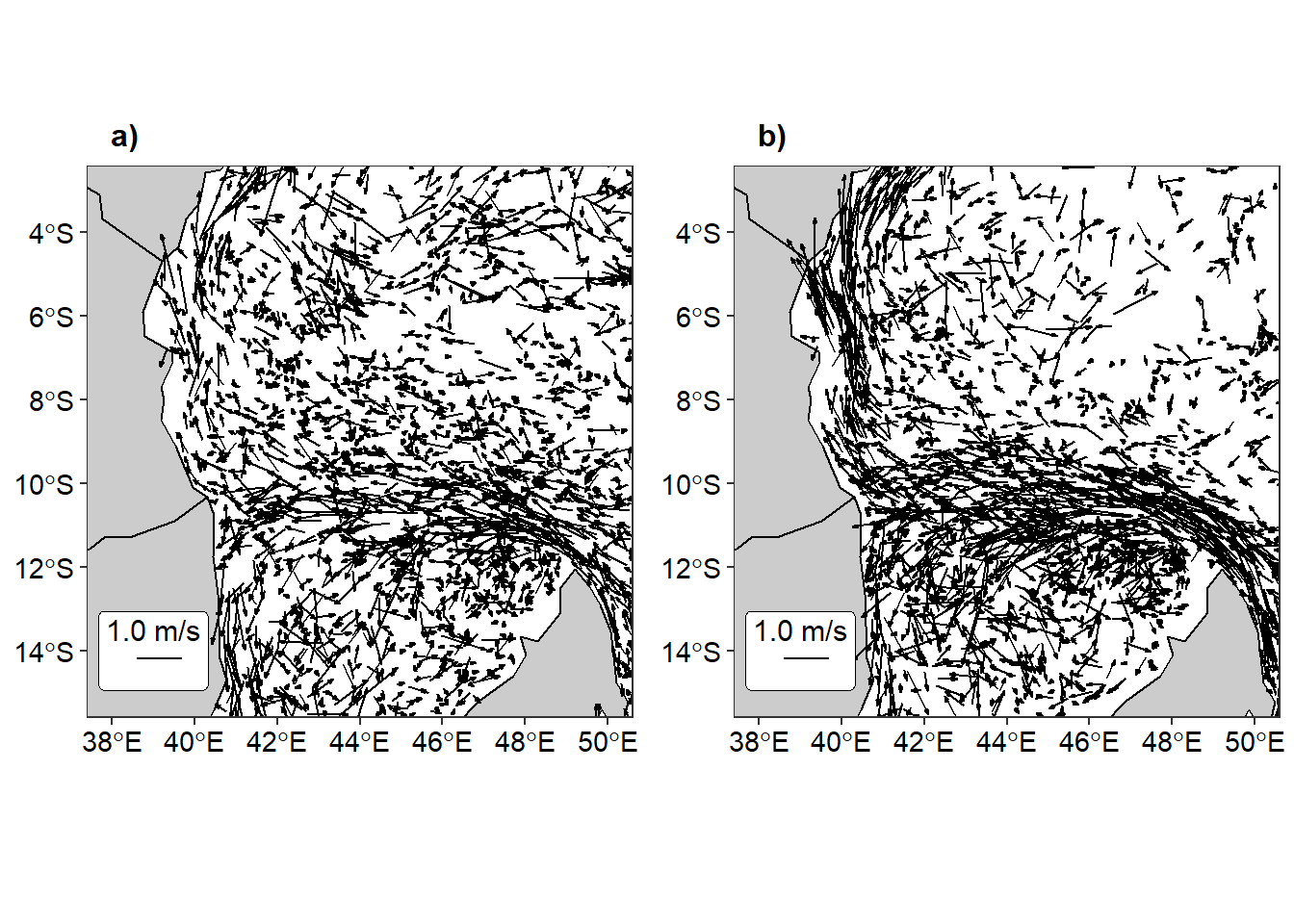

Figure 1 show Surface current vectors compiled from drifters. The South Equatorial current and East African Coastal Current are more prominent during the southeast monsoon season (Figure 1) compared to the northeast season (Figure 1). This observation matches those reported by Barale6 described that the South Equatorial Current, flowing westward with the Trades north of 22 oS, divides into a north-flowing stream that feeds the northward East Africa Coastal Current, and a south-flowing stream that feeds the East Madagascar Current. The East African Coastal Current runs northward throughout the year between 11 \({^\circ}\)S and 3 \({^\circ}\)S.

Figure 1: Surface current from drifter observations a)northeast, b)southeast monsoon season

Drifter observation in figure 2 reveals the same picture that the northern branch of the south equatorial current (SEC) in the Indian Ocean passing through the northern extremity of Madagascar Island and continuing westward to the coast of Africa near 11 \({^\circ}\)S. There it splits into the north-flowing East African COastal Current (EACC) and a branch flowing south into the Mozambique Channel. The comparison of surface current in the tropical Indian Ocean suggest that most of the water of the South Equatorial Current goes into the East African Coastal Current than Mozambique Channel (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Surface current flow in the tropical Indian Ocean

Like previous studies, drifter reveals clearly the EACC as part of the boundary current system off the East Africa, which flows northward both in northeast (Figure 4) and southeast monsoon season (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Surface current flow during the southeast monsoon season

Figure 4: Surface current flow during the northeast monsoon season

Conclusion

Surface current vector (Figure 1) and surface current trajectories (Figure 3 & 4) reveal the previous studies focused on the east african coastal current and south equatorial current. However, the drifter observation show much detailed pathways of the surface current during the southeast and northeast monsoon season.

Cited References

Nyandwi, N. (2013). The Effects Of Monsoons on the East African Coastal Current Through the Zanzibar Channel, Tanzania. The Journal of Ocean Technology, 8(4), 65-74.↩

Huntingford, G. W. B., The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, 225 pp.,Hakluyt Society, London, 1980.↩

Lutjeharms J.R.E., A Guide to Research Done Concerning Ocean Currents and Water Masses in the South West Indian Ocean,577 pp. University of Cape Town, South Africa, 1972↩

Wyrtki, K., Oceanographic Atlas of the International Indian Ocean Expedition, 531 pp., National Science Foundation, Washington,D.C., 1971↩

Citeau, J., B. Piton, and Y. Magnier, Sur la circulation g6ostrophique dans l’ouest de l’oc6an Indien sud-equatorial, Doc. ORSTOM 31, 32 pp., Inst. Fr. de Rech. Sci. Pour le Develop. en Coop., Brest, France, 1973.↩

Barale, V. (2014). The African Marginal and Enclosed Seas: An Overview. In V. Barale & M. Gade (Eds.), Remote Sensing of the African Seas (pp. 4-29): Springer Science.↩